What is demeanour and why would we measure it?

Demeanour is defined as “outward behaviour or bearing”. When looking at the demeanour of an animal, we are referring to the outward expression of how that animal is feeling and expressing itself at a given moment. Assessing demeanour is something that animal care staff will generally do inherently with the animals they are caring for. For example, you check on the animal when you get to work and just know something is “off” with them, and you call the vets and monitor them closely. What we are going to be exploring in this article is not just assessing demeanour when something is off with the animal, but intentionally assessing demeanour daily or periodically to gain insight into the animal’s overall wellbeing.

As I have already mentioned, assessing demeanour is inherent for many animal care staff, it is very common at care and welfare meetings for keepers to explain a sort of “demeanour profile” that they have come up with over time, telling others at the meeting how this animal behaves at all hours of the day. Formalizing this process into measurable and agreed-upon assessments and profiles can help eliminate discrepancies between care staff and turn this already honed skill into something that can produce invaluable data for welfare assessments. Too often are welfare assessments only focused on quantitative data like weights, exhibit size and health records, but qualitative data about an animal’s mental state can be extremely important to create a “full picture” of an animal’s welfare state.

“If we rely on qualitative judgements in daily life, but then ban those judgements from science, we risk creating an artificial separation of scientifically constructed and personally experienced realms of understanding”

Midgley, 1983

A lot of the time, facilities focus on tracking welfare “inputs”, things like the enrichment we are providing, the training we are doing, and the animals we are pairing together; outputs, essentially the perceived welfare these inputs are providing are much harder to track. Demeanour is a great output to track and one that will ultimately help you in getting to know your animals better.

A note on teamwork and abstract objectives/ goals

Assessing the demeanour of an animal is something I like to call an “abstract objective” meaning it is not a “yes or no” objective. For instance, did the Tiger interact with the boomer ball? Is a “yes or no” goal, it is not up for interpretation or discussion, it is easy to answer. What was the demeanour of the tiger like while they interacted with the boomer ball? By contrast, this question has a lot to interpret and discuss and might not be straightforward to answer. Questions like these take discussions from the whole team to ensure consensus and accuracy in the long term. If five members of your team are on the same page with what stress looks like in a fox, but the sixth person on your team is interpreting stress as play behaviour, then your whole data set will be thrown off. A robust animal welfare program comes from including everyone’s opinions and observations, so it is not the goal of this to silence anyone, but instead, to get as close to a consensus as possible on behavioural observations to ensure accuracy.

Assessing demeanour vs behaviour

At this point, some people may be wondering what the difference between assessing demeanour and behaviour is. When you are assessing an animal’s behaviour, it is usually done in the form of an ethogram or an activity budget to get an overall idea of how an animal behaves throughout the day. Assessing demeanour on the other hand is trying to figure out what that behaviour means and ultimately get an idea of an animal’s mental state. For example, your activity budget for the day might look the same regardless of whether or not you are in a positive mental state (happy, content, optimistic) or a negative mental state (depressed, burnt out, under the weather); you wake up at the same time, eat at the same time, drive to work at the same time, go to sleep at the same time. What is different is how you experience that day, interact with others and interpret events and experiences. This same concept also applies to other animals and has been studied in domestics such as dogs (Wemelsfelder, 2007). Researchers have even gone a step further by studying “optimistic cognitive bias” in rats (Brydges et al.,2011). They found that rats that were exposed to enriching environments perceived negative experiences with a bias toward optimism compared with rats that were not housed in enriching environments. This has great implications for zoo-housed animals as we can foster these optimistic biases and make their welfare states more robust and resilient when it comes to facing inevitable negative situations like vet visits or moving facilities.

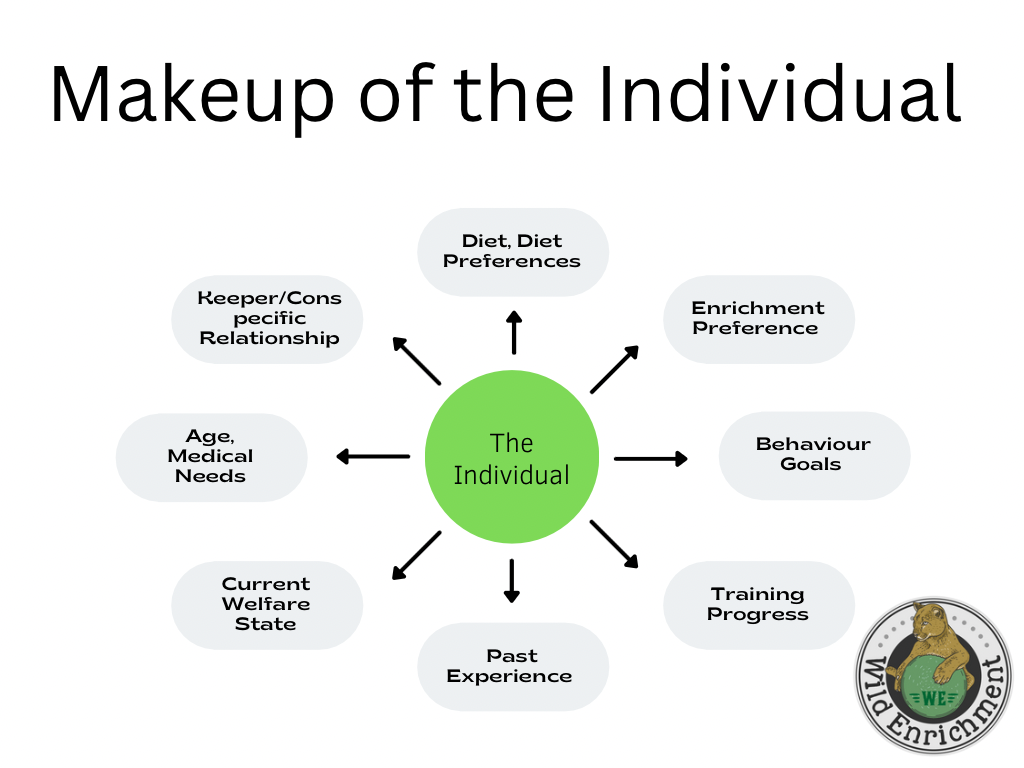

Don’t forget the Individual

“When observers spend hours recording behaviour, they end up not only with behavioural data but with clear impressions of individuals”

Stevenson-Hinde et al 1980, p 66; Stevenson-Hinde 1983

I have talked about the importance of thinking about animals as individuals and not just as a projection of their wild counterparts and this is an important factor to consider when looking at demeanour. However you choose to assess and record demeanour, there must be room for individuality to shine through for the animal, especially if it’s being housed in a group setting. The more you and your team learn about the animals in your care as individuals the more their care can be modified to suit them as an individual. According to researchers, many animals can in fact have a measurable “personality” that persists over time, similar to what we call a personality in humans (Wemelsfelder, 2007). The goal of measuring personality and demeanour is not to create an anthropomorphic data set by saying things like “sad” or “confused” but instead to create an idea of what these emotions might look like if the animal were to express them.

When to assess demeanour

In an ideal world, where keepers had endless amounts of time, assessing demeanour would be done daily on every single animal at a facility, but this would take an immense amount of time and for many animals, wouldn’t produce actionable data. Realistically, closely observing and recording demeanour should be reserved for specific situations where animal welfare needs to be closely monitored daily. Some examples:

- Before and after an introduction

- Getting an idea of the demeanours of individuals in a group and group dynamics before introducing a new individual would be useful.

- Monitoring the demeanour of group members after an introduction making sure welfare states are maintained across the group.

- Aged animals/ Quality of life monitoring

- As an animal gets to an advanced age or its quality of life is in question, monitoring its demeanour daily can be very useful.

- Getting a baseline on an animal

- Sometimes getting a baseline demeanour on an animal and coming back at a later date to compare is a great way of seeing changes you may have missed.

How to assess demeanour

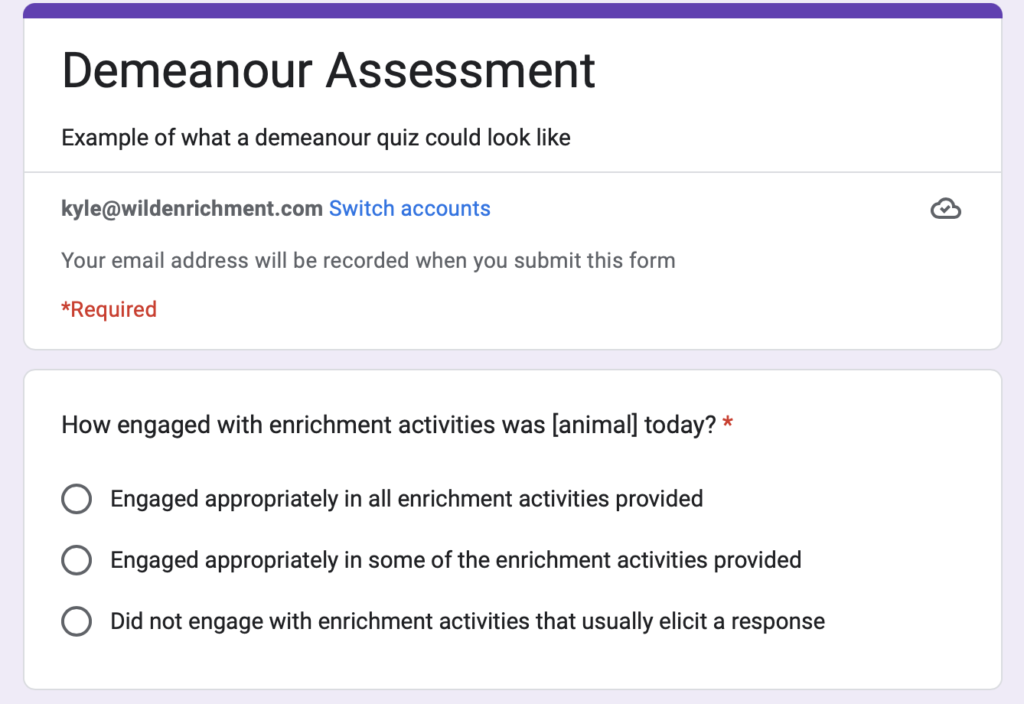

The easiest way I have found to assess an animal’s demeanour is to design a multiple choice “quiz” that keepers can take daily during their observations of an animal. There are a few advantages of this approach, the first being that multiple choice allows some consistency with answers/ word use, making the data easier to look over, questions can also be designed in such a way that it tells the assessor what to look for and when to look for it. Designing these quizzes is also a great way for care teams to talk about the animal in question and come to a consensus where possible. These quizzes can be set up via Microsoft forms or Google sheets and the answers can be put into a spreadsheet after for further analysis. The main thing you are looking for here is consistency, accuracy and accessibility for everyone on the care team.

Some easy things to focus on in the beginning are engagement with keepers and situations. Engagement is an easy thing to define and an easy thing to assess right away. For example:

- How engaged was [Animal] during your training session?

- Very engaged

- Engaged most of the time

- Not engaged

- How engaged with you was [animal] during the AM servicing?

- Focused on what I was doing the entire time I was servicing the exhibit

- Engaged with me most of the time

- Not engaged with me, otherwise engaged with the environment

- Despondent, not engaged with me or the environment

- How engaged with enrichment activities was [animal] today?

- Engaged appropriately in all enrichment activities provided

- Engaged appropriately in some of the enrichment activities provided

- Did not engage with enrichment activities that usually elicit a response

Regardless of the question, they need to be important and relevant for the animal in question, if the animal does not usually engage with keepers then the question is not useful. Questions should also be species-specific when it comes to behaviour for example:

- Did you observe any of the following negative behaviours today?

- Did you observe any group interactions today between [animal] and the group?

When analyzing your data the main things you are looking for are trends and patterns as well as deviations from these patterns. For example, if the animal you are working with is typically very engaged and greets you in the morning and you see the data drifting toward not being engaged as well as a lack of engagement in other areas then that might be indicative of a larger problem going on. Or if you are planning to introduce a new animal to a group and you notice that one individual in the existing group is much more relaxed and tolerant of other individuals, that might help inform your introduction plan.

In conclusion, assessing and recording the demeanour of the animals you are working with can lead to extremely useful information that can help inform decisions about introductions, quality of life and overall welfare. This type of assessment is something that keepers are already inherently good at and doing regularly, the process of formalizing it is what makes this a useful and worthwhile process. Having this data available to you can help speed up meetings (or eliminate them altogether) and help with decision-making within a team. All it takes is teamwork, creativity and a bit of time spent watching animals.

References and further reading

- Andreasen, S. N., Wemelsfelder, F., Sandøe, P., & Forkman, B. (2013). The correlation of Qualitative Behavior Assessments with Welfare Quality® protocol outcomes in on-farm welfare assessment of dairy cattle. Applied Animal Behaviour Science, 143(1), 9–17. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.applanim.2012.11.013

- Brydges, N. M., Leach, M., Nicol, K., Wright, R., & Bateson, M. (2011). Environmental enrichment induces optimistic cognitive bias in rats. Animal Behaviour, 81(1), 169–175. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.anbehav.2010.09.030

- Walker, J., Dale, A., Waran, N., Clarke, N., Farnworth, M., & Wemelsfelder, F. (2010). The assessment of emotional expression in dogs using a Free Choice Profiling methodology. Animal Welfare (South Mimms, England), 19, 74–84.

- Wemelsfelder, F. (n.d.). How Animals Communicate Quality of Life: The Qualitative Assessment of Behaviour. 12.

- Wemelsfelder, F., Hunter, A. E., Paul, E. S., & Lawrence, A. B. (2012). Assessing pig body language: Agreement and consistency between pig farmers, veterinarians, and animal activists1. Journal of Animal Science, 90(10), 3652–3665. https://doi.org/10.2527/jas.2011-4691